Other low-cost manufacturing hubs, hoping to ship more goods to the locked-down US and EU, are reportedly now muscling in on the established China-Northern Europe route, meaning that any available ships and containers are being diverted to parts of Africa and South Asia.

With ports in the EU and the US at capacity in terms of the number of containers they can take, ships stuck in ports or lacking a crew, and warehouses either unstaffed because of lockdown measures or, as in China, perennially oversubscribed, companies are electing to store their goods in containers, limiting supply even further.

This briefing will explain why it has become more difficult for companies to secure containers to ship goods between the UK and China, the impact this is having on industry, and the steps that companies and governments are considering to reduce its impact.

Background

The shipping industry can perhaps best be conceptualised by imagining a Russian doll: The commodity the consumer wants moved is itself transported inside a series of other commodities: ships, shipping containers, cardboard boxes, the consumer good. Covid-19, and the lockdowns most markets have introduced to curb its spread, has resulted in each of these commodities attracting premium prices because they are all in high demand.

There is no easy way to resolve this problem. For example, expanding the global supply of ships would take at least three years due to the time it takes to build new ones. Similarly, increasing shipping container supply is tricky while the factories that manufacture them – and their suppliers– are affected by widespread lockdowns. Shipping companies are anyway reluctant to order more containers, given that that the problem isn’t so much with supply — it’s more that the world’s containers aren’t currently where they are most needed.

So where are the shipping containers?

The established trade routes of pre-pandemic times have been distorted to reflect the markets that are open for manufacturing and those that are open to taking more cheap consumer goods. As a result, the bulk of the world’s shipping containers appear to be in one of three places:

- Stuck in the EU or the US: China came out of lockdown as the EU and the US entered lockdown. As people resigned themselves to spending more time at home, there was a surge in demand for consumer goods that are often manufactured in China, leading China’s shipping companies to send more ships and containers to these markets. However, there has been little or no incentive to return the shipping containers to China; with economic activity in large parts of the EU still limited, many of the containers would likely return empty.

- Stuck in China: China’s warehouse storage is oversubscribed, meaning that companies that are unable to export goods because the US/European ports are at capacity have little choice but to store stock in any available containers, usually portside, until the West comes out of lockdown and this congestion can start to be cleared.

- On ships diverted to Africa and South Asia to serve the US and EU markets: Low-cost manufacturing hubs across Africa and South Asia are reportedly vying to supply high levels of demand for consumer goods in the US, meaning that containers are increasingly stretched across competing supply chains.

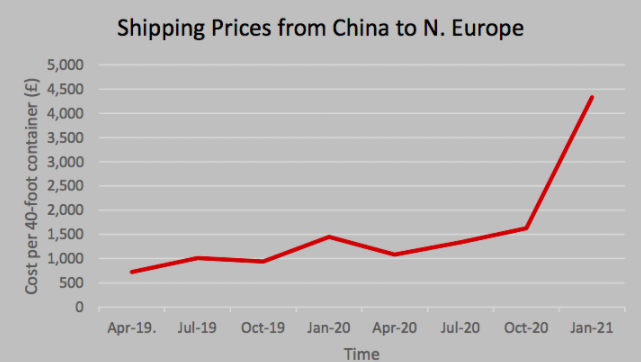

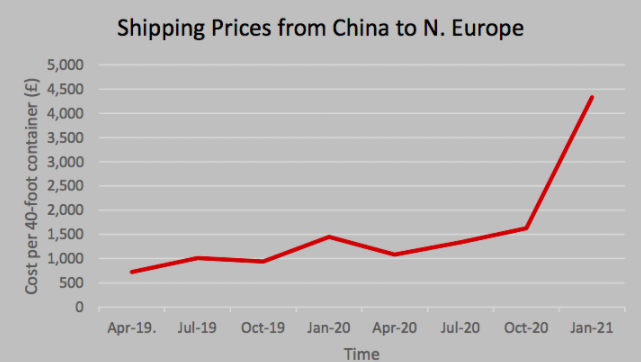

All three outcomes result in the price of shipping increasing because there is greater demand and less certainty regarding shipping times, costs and loads. So even though demand for international shipping dropped overall by as much as 14% in volume and 21% in value last year, according to the World Trade Organization, a container that before the pandemic cost around £600 to ship from Harwich to Shanghai is now going for as much as £4,500.

How is it impacting industry?

Shipping companies are reportedly passing on costs incurred by holding containers at ports for longer through extra fees. Companies must then either absorb the increase in costs or pass it on to consumers, which might make their price points uncompetitive.

UK companies are beginning to report that the increase in shipping costs means they are making a loss on some sales; importing from China is, in turn, becoming a less viable business model. The UK’s Association of Domestic Appliances has said its members have reported increases in shipping costs of up to 300% since the start of 2020. “Signs of strain are building up and the situation is likely to intensify before it eases,” according to Capital Economics.

The picture is no prettier in China. Aware of the fact that shipping a container to the UK or Europe is not likely to make financial sense, come January shipping companies in China had reportedly began charging as much as £10,000 to ship a 40ft container that used to go for around £2,000 to the UK.

How is it impacting consumers?

Companies appear unwilling to push increased shipping costs onto consumers with markets for consumer goods currently so competitive. Shifting costs to consumers is anyway not always possible, especially if the company operates in business-to-business logistics or offers an end-to-end delivery model where contracts are drawn up months in advance, with liability for shipping costs often factored in. A particular issue currently is that the backlog caused by the pandemic goes back into 2020, meaning that companies are struggling to honour contracts drawn up when the cost of shipping was a third of what it is now.

Still, it looks like consumers will only be able to avoid higher prices for so long, with economists predicting that supply shortages and higher freight rates will restrict trade growth and contribute to temporarily higher inflation pressures over the course of the year.

What are Governments planning to do about it?

CBBC has made enquiries to both the British and Chinese Governments and has ascertained that both are aware of the rising cost of shipping and are seeking to remedy the issue.

China has reportedly been subsidising its shipping companies to bring back containers from the US or Europe empty because it is worried that the pile-up is putting its position as the preferred low-cost manufacturing hub in jeopardy. Of course, this is making it harder for US or European companies that are able to export to get hold of containers. In addition to this, at a press conference held by Li Xingqian, head of foreign trade at the Ministry of Commerce (MOCFOM), in January, it came to light that MOFCOM and the Ministry of Transport have been considering applying anti-trust measures against shipping companies in a bid to keep costs down, as well as other steps aimed at stimulating vessel supply, such as putting pressure on foreign shipping companies to resuming sailings that they had suspended due to poor profitability.

The CBBC understands from those with knowledge of the situation that it would be difficult for the UK Government to introduce measures aimed at controlling the increasing cost of shipping to China, and not only because the UK is a free-market economy. The risk is that subsidising the cost of shipping between the UK and China would further artificially adjust trade flows and could, in effect, subsidise Chinese exports to the UK to the detriment of UK manufacturers.

CBBC View

CBBC is aware that in an environment where costs are on the rise across the board, increases in shipping prices are having a particularly detrimental impact on the ability of UK firms to trade with China. Companies of all sizes need to move goods between the two markets, be they large multinationals exporting parts for assembly or small wholesalers in the UK that source the bulk of their merchandise from China. The CBBC will continue to monitor this issue and aim to keep members informed following any conversations it has with the British and Chinese governments and any other relevant stakeholders.